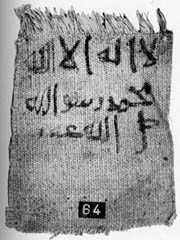

| 4.a.1. Papyrus: |

The plant:

- Cyperus papyrus l. in Latin, bardî,

abardî or fâfîr, babîr and barbîr

(from Greek papyrós) in Arabic.

- Papyrus was grown of course in Egypt (especially

the Nile Delta), in Palestine, Babylonia and Sicily. Around the 11th

century papyrus stopped being used as writing material and became a

rare plant in these regions [Abu 'l-Abbâs al-NABÂTÎ,

13th century].

- The material extracted from the plant and used

for the papyrus is called qirTâs (from Greek xartês),

waraq al-qaSab or waraq al-abardî.

|

PAPYRUS PLANT

near Syracuse

[high resolution] |

|

|

The production:

- First the papyrus cane was cut lenghtways into

two halves. Then strip after strip

was removed from the medulla, the inner strips having a higher quality.

- These strips were then laid crosswise in two

layers, a horizontal one lying on top of the vertical. Then they were

pressed (either with or without an adhesive made of seeds of the blue

lotos (Nymphaea coerulea Sav.).

- After the pressing the sheets were smoothed

out with a wooden stick.

|

|

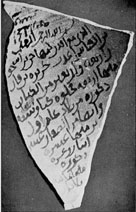

The sheets:

- They had an average size of 25 cm (width) x

20 to 58 cm (length), but were in no way uniform.

- The single sheets were stuck together,

often 20 in numbers, the right side of the first overlapping the left

side of the following. Mostly no cross pattern was seen afterwards.

- The first sheet was normally integrated in a

inverse manner - i.e. the fibres lay in a right-angle to the horizontal

fibres of the rest of the roll - for the following reasons:

- for the cover it looked nicer and provided

a better protection, as it was made of a thicker and coarser material.

This cover sheet was often used as the space for the protocols.

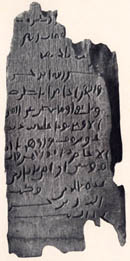

- the protocols: the protocol texts were used

for standard religious formulas, the

name of the caliph or another magnate, the name of the manufacturer

and the place of manufacture - based on the model of the Latin-Greek

emperors.

In pre-Islamic times the protocol served as proof of authenticity,

but in Islamic times it was prescribed by the government. It thus

seems to have served as a control for the state.

|

|

The manufacture:

- The manufacturers naturally delivered the papyrus

in form of rolls. This roll is called qirTâs in Arabic

(from the Greek xartês), a sixth of it being the tûmâr

(from Greek tomárion). The roll could be divided into

smaller parts, such as thirds, fourths, etc.).

- This division was made for practical reasons,

because writing to persons of different social status demanded distinct

sizes of papyrus. The following examples show the conditions in the

time of the Umayyads, who preferred to use papyrus in their chancellery:

| - letter to the caliph: |

2/3 tûmâr |

| - letter to a governor: |

1/2 tūmār |

| - letter fo financial governors

and state secretaries: |

1/3 tūmār |

| - letters to traders: |

1/4 tūmār |

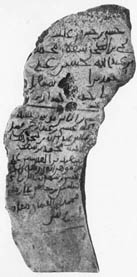

- For Islamic times there are in contrast to

classical sources just rare descriptions of the consistence of the different

papyri. High quality products are the exception. A look at the existing

papyri shows a range from fine to coarse and from yellow to brown in

all shades.

- The high quality papyrus was very expensive

(e.g. in the 8th century it cost about 1.5 dînâr

- equal to the annual rent of a shop).

- These high costs made people use the papyri

several times, either by washing

out the scripture or more often by using the back-side.

In higher social classes this certainly wasn't regarded as good form.

- Finally, the papyrus was first used on the side

with horizontal fibres, because this was the finer one, and just on

less important occasions on the side with vertical fibres, the coarser

one.

- The front with its horizontal fibres is called

recto in papyrology, the back with its vertical fibres is called

verso.

|

| |

| al-sulaymānī: |

named after SULAYMÂN B.

RASHÎD, financial supervisor of Khorâsân under HÂRÛN

AL-RASHÎD (786-809 AD) |

| al-TalHî: |

named after TALHA B. TÂHIR,

governor of Khorâsân (822-28 AD) |

| al-nûHî: |

named after NÛH B. NASR,

samanid ruler of Khorâsân and Transoxania (942-954 AD

) |

| al-fir‘awnî: |

supposedly a designation for marking

the competition with Egypt in the production of papyrus |

| al-ja‘farî: |

named after the wazîr JA‘FAR

B. YAHYÂ B. KHÂLID B. BARMAK, governor of Khorâsân

for a short time in 796 AD who introduced paper into the main chancellery

|

| al-Tâhirî: |

named after TÂHIR B. ‘ABDALLÂH,

ruler of Khorâsân (844-862 AD ) |

|

|

|

Spreading:

- Starting in the 10th century a number

of capital cities within the Islamic world started to produce their

own paper: Damascus, Tripoli, Baghdad, etc.). In Egypt this process

started by all accounts at the end of the 11th century, but

Egypt also seems to have imported paper from "frankish" countries

(i.e. Italy and France).

- The reason for the growing use of paper lies

in the fact that it is less vulnerable to forgery (in contrast to the

papyri or the parchments, which could be washed out or scraped off and

rewritten without leaving traces).

- This paper still contained rags (often linen),

mixed with other material like hemp (Cannabis

Sativa L.) or small amounts of lamb wool.

- The quality of the paper was generally higher

in the east than in the west. The highest quality came from Baghdad.

Steps of production:

- The raw material (linen rags, hemp, etc.)

was cut up, cleaned and washed in lye.

- Then it was expanded by adding water, bleached

and crushed after removing the water or in a paper mill ground.

- This intermediate product was dissolved in

water and then put to a wide tub containing a sieve.

- In this tub the mush was mixed up thoroughly,

and then ladled with a special sieve (KARABACEK found three such forms,

all consisting of a wire mesh held together by a wooden frame).

- The paper was then removed from the mesh and

tacked upon a wall.

- In the next step it was impregnated with a

paste of flour and thickening agents and then dried. This procedure

was repeated several times.

- The paper sheets were now pressed between

two planks and smoothed with a polishing stone of glass or agate.

- Finally it was impregnated again with rice

or wheat extracts diluted in water and smoothed once again.

Colours:

- The paper could be dyed as well with the following attested colours:

- red: cinnabar or ochre (dissolved varnish

of the scale insect)

- rose coloured: al-waraq al-muwwarad,

al waraq-al-‘ûdî (dyed by a brew of brazil

wood)

- blue: indigo, cobalt or aloe

- yellow: saffron of a brew of lemon skin

(Cortex limonis)

- or simply a mixture of various colours

| ! |

PAPER SHEETS:

the paper was sold in separate sheets, mostly in a dast of

25 sheets, or in a rizma (with five dast each). It was

sold in rolls too. |

! |

|

| 4.b.1. The Reed

pen: |

Name:

- In Arabic called qalam (from Greek kálamos) or

mizbar.

- Used by the Arabs for many centuries.

|

ARABIC REED PEN

from al-Fustāt

[high resolution] |

|

Occurence:

- The best pens came from the reeds of the Egyptian

swamps.

- Pens from the Persian province Fârs, and

the Nabataean reeds are considered to be of high quality as well.

|

|

|

Characteristics:

- There were different kinds of pens: thick and

thin ones, hard and soft ones, having grown on rocky or swampy

soil: each was used for a distinct purpose.

- The average thickness of the qalam is

between the size of a forefinger and the size of a little finger

[according to the famous calligrapher IBN MUQLA].

|

|

Preparation:

- Special importance is in the cutting of the

reed, particularly in its rounded cut part (jilfa) and the cutting

of its top. This art was often kept secret because "the writing

depends on the qalam" [according to the calligrapher AL-DAHHÂK]:

- The cut part (jilfa, khurTûm

) had to be long (about the length of a thumb joint or a

pigeon beak) [according to the calligraphers IBN MUQLA and IBN AL-BAWWÂB].

- The point of the qalam should be

thin like "lips" (i.e. tips) of a pigeon's beak [according

to the calligrapher JA‘FAR B. YAHYÂ’]; the right

side of the point should be higher than the left one [according

to the calligrapher IBN ‘ABD AL-HÂMID B. YAHYÂ].

- The pens usually were split in the middle

(as shown in some pens found in Edfû and in the writing itself

- which is doubled in some parts.

|

|

Vessel:

- The qalam was kept in a writing vessel

(dawât), containing besides the qalam the following

objects:

- a penknife (mudya, sikkîn)

- a cutting plank (miqaTT, miqaTTa)

- a sprinkle box for sand (mitraba, mirmala)

- an ink wiper (mimsaHa, daftar)

- a whetstone for sharpening the penknife

(misann)

- a sea-shell or a copper vessel (misqât)

for pouring water, sometimes rosewater (mâwardîya)

into the inkwell

- a wooden ruler (misTara)

- a piece of wool or linen as blotting pad

(mifrasha)

- the inkwell (miHbara), which was

a round vessel (jûna) with a pad of wool, linen or

raw silk soaked in ink (lîqa), which was renewed every

month

- the spatula (milwâq) for the

change of the lîqa

- A different kind of writing holder was carried

on the writer's belt with the inkwell and the pen case (miqlama)

made of one piece.

WRITING VESSEL

of Sultan Salāh al-Dîn

(1362 AD)

[high resolution]

|

| 4.b.2. The ink: |

Name:

- In Arabic called midâd.

- The documents show mainly two kinds of ink:

- a deep black ink, similar to Chinese ink

(duhn Sînî, duhn and Hibr). It

contained mainly fine soot or similarly treated charcoal

- a more russet ink, containing large parts

oxidized iron, similar to the ink made of gallnuts

|

|

Preparation [as described by al-Qalqashandî]:

- At the time of the Tulûnîd Khumârawayh

(884-96 AD) a black ink was made in this

way:

- oil of radish and flax seeds

was added to a burning lamp and covered by a bowl

- when everything had burned down, there remained

a fine film of soot in the bowl

- this soot was mixed with rubber and myrtle

water, which gave a greenish tinge to the

black colour

- The ink made of gallnuts, often used for papyri,

was prepared in this way:

- 1 pound of Syrian gallnuts was crushed and

put in a pot with boiling water

- after cooking, 3 ounces of Arabian

rubber and 1 ounce of ferric sulphate

were added

| ! |

INK:

when this ink runs low in the qalam,

the writing appears in a brown yellow

shade. |

! |

|

|

Colours:

- Besides the black ink there existed different coloured inks:

- red ink: made of cinnabar (zunjufr)

made of an extract of pomegranates or of red chalk from the Irak

(maghrâ ‘îrâqî)

- green ink

- blue ink: made of lapis lazuli

mixed with water and rubber

| ! |

INK AND PAPER:

the russet coloured ink could destroy

the document (papyrus, paper, etc.). This never happened with black

ink. The red ink faded fast. |

! |

|